Leila Lax, B.A., B.Sc.AAM, M.Ed.

Ian Taylor, M.B., Ch.B, M.D

Linda Wilson-Pauwels, AOCA, B.Sc.AAM, M.Ed., Ed.D.

Marlene Scardamalia, Ph.D.

Knowledge building theory (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2002) and Knowledge Forum®, a Web-based, asynchronous, collaborative learning environment, were integrated in a face-to-face medical legal visualization course in the biomedical communications program at the University of Toronto (U of T). Iterative design critiques, new software tools, and the concept of building on ideas created a synergy of enhanced interactions and outcomes, resulting in idea innovation. The novel concept of “dynamic curriculum design” was introduced and found to support student efforts to advance the current edge of knowledge.

Introduction

The culture of teaching and learning in the Master of Science program, offered by the Division of Biomedical Communications (BMC), in the Faculty of Medicine at the U of T, has evolved over the years to keep pace with current pedagogic techniques. The traditional pedagogic culture embodies strong constructivist methods based on the Deweyean philosophy of “learning by doing” (Dewey, 1938), to overcome “inert ideas” (Whiteside, 1929). Small group, constructivist learning methods have been favored over large group, didactic techniques (Tiberius, 1990). Constructivist learning theory has prompted transition from teacher-centered feedback to interactive, student-centered group critiques (Donovan et al., 1999). The critique is the hallmark of teaching and learning in most BMC graduate courses. One-on-one critiques (dialogues between student and teacher), and group critiques are common. Constructive criticism provides students with timely feedback for progressive refinement of ideas. A comprehensive medical art critique includes feedback on the visual representation of ideas, and accuracy of scientific/medical information, as well as feedback on interpretation of the concepts.

Various aspects of constructivism, such as self-directed learning (Knowles, 1975), evidence-based learning (Sackett, et al., 1997), and reflective learning (Schon, 1987) are evident throughout BMC curricula. Recently, knowledge building theory (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1993; Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2002), a cutting-edge constructivist learning approach, and Knowledge Forum®, a Web-based, asynchronous, collaborative learning environment were introduced in a second year M.Sc.BMC course titled Medical Legal Visualization (Figure 1). Knowledge building theory and Knowledge Forum® were initially integrated in this face-to-face course in the winter/spring session of 1999. Successful blending of face-to-face learning and online knowledge building methods led to sustained use of eLearning technology in this course. Continuous improvements in knowledge building curriculum design contributed to higher level student outcomes over the past five years.

This paper examines collaborative knowledge building by the medical legal visualization class of 2003. Iterative design critiques, new software tools, collaboration, and the concept of building on ideas created a synergy of enhanced pedagogic interactions and outcomes, resulting in dynamic innovations in medical legal visualizations. Results of a 2003 survey of students’ attitudes and opinions strongly supports use of the collaborative knowledge building approach and blended learning (face-to-face and online) in this BMC course. The pedagogic culture of this course and of the BMC graduate program in general, provides unique opportunities for combining didactic and emergent curriculum design, allowing for knowledge transfer and creative work with new ideas.

Knowledge Building

Scardamalia & Bereiter (2002) define knowledge building as “the production and continual improvement of ideas of value to a community.” Knowledge building goes beyond traditional learning to recognize the importance of creating new knowledge and advancing beyond current best practices (Bereiter, 2002). Knowledge building provides a framework for collaboration and development of diverse ideas. Individual accomplishment raises the level of the entire contributing community. Knowledge building theory extends the pedagogic agenda beyond the highest level of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (1956), from evaluation to advancement of knowledge.

The socio-cognitive dynamics of knowledge building are supported by the technical opportunities afforded by Knowledge Forum®. Knowledge building theory is defined by Scardamalia (2002) as a system of twelve principles that interrelate socio-cognitive and technical dynamics. The principles of knowledge building are listed below with examples from the BMC students’ Knowledge Forum® 2003 database, which includes sketch, rendering, and final critiques.

Culture of Knowledge Building Collaboration

Knowledge building theory incorporates numerous principles to create an overarching learning culture. Individual components of this culture are addressed below.

Figure 2. Idea improvement through text and images

Figure 2. Idea improvement through text and images

Figure 3. Authentic cases and primary evidence

Figure 3. Authentic cases and primary evidence

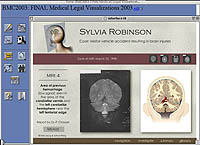

Figure 4. Shared responsibility for conceptualization, interface design and rendering

(© 2003 Danielle Bader, Julie Saunders, and Shelley Wall)

Figure 4. Shared responsibility for conceptualization, interface design and rendering

(© 2003 Danielle Bader, Julie Saunders, and Shelley Wall)

Figure 5. Within note multi-referencing to support idea convergence

Figure 5. Within note multi-referencing to support idea convergence

Figure 6. Ideas in Knowledge Forum® can be represented in text and images

(© 2003 Jason Raine)

Figure 6. Ideas in Knowledge Forum® can be represented in text and images

(© 2003 Jason Raine)

Figure 7. Feedback from medical content expert

(© 2003 Dr. Ian Taylor, © 2003 Doris Leung and Janice Wong)

Figure 7. Feedback from medical content expert

(© 2003 Dr. Ian Taylor, © 2003 Doris Leung and Janice Wong)

Figure 8. Feedback from experts located at a distance

(© 2003 Sue Seif and Associates, © 2003 Marlene Herbst Loth)

Figure 8. Feedback from experts located at a distance

(© 2003 Sue Seif and Associates, © 2003 Marlene Herbst Loth)

Idea Improvement

Progressive improvement of ideas is a key knowledge building principle.

Knowledge Forum® allows for the continual refinement of ideas and information

represented in text and images. Each revision is archived, which provides

a traceable history of development. This archive is used for reflection,

evaluation, and further learning (Figure 2).

Authentic Problems

An authentic personal injury case is used in this BMC course. Students

are provided with the original medical and psychological reports, including

magnetic resonance images (MRIs) (Figure 3). They conduct neuroanatomical

research, then create representations of various conceptualizations in

the layout, design, and rendering phases. Ultimately, they create a visual

artifact intended to help a lay audience understand the evidence.

Community Knowledge/Collective Responsibility and Democratizing Knowledge

Teamwork is supported through collaborative interaction both online and

offline (Figure 4). Students are given the option to work individually

or in small groups. Those who opt to work individually share in and benefit

from the collective responsibility of providing feedback and constructive

criticism. All students post their medical legal artwork in Knowledge

Forum® at intervals throughout the development of their projects. Ideas

and techniques are shared online (Figure 6). Collaborative, constructive

problem solving characterizes online critiques. In reality, no one works

in isolation and everyone benefits from the knowledge shared via text

and images. The process effectively creates a community of knowledge builders

collectively responsible for the overall advancement of the group. Contributions

are distributed and highly democratic. As one student noted, it is often

the quiet ones in regular classes who say the most profound things online.

Idea Diversity and Rise-Above

Community knowledge is characterized by idea diversity. Scardamalia (2002)

states, “Idea diversity is essential to the development of knowledge

advancement… To understand an idea is to understand the ideas that surround

it, including those that stand in contrast to it. Idea diversity creates

a rich environment for ideas to evolve into new and more refined forms.”

Various ideas in different notes contributed by students can be hypertext

linked in one note to synthesize and advance diverse and similar ideas

in the collaborative online critique process. These multilinking, multireferencing,

and rise-above functions are distinguishing features of Knowledge Forum®

that support high level collaborative interaction. Such interactions are

usually at a higher level than those typically seen in threaded discourse

environments (Figure 5). Threaded discourse is conceptualized in a discussion

framework of individual posts and responses, whereas knowledge building

discourse is centered around collaborative synthesis, linking, and advancement

of ideas. Knowledge Forum® provides higher level technical affordances,

including the ability to work with multiple ideas represented in text

and images, to enable the possibility of higher level socio-cognitive

outcomes.

Pervasive Knowledge Building, Constructive Use of Authoritative Sources,

and Symmetric Knowledge Advancement

In Medical Legal Visualization, knowledge building is the pedagogic approach

used both online and offline; it is pervasive. Knowledge Forum® discourse

and visual updates are central to course work. The Knowledge Forum® learning

environment extends community connections and provides opportunities beyond

the classroom. It is not used as an add-on to learning; it is where the

learning happens, anytime and from anywhere. Individual students are connected

to other students, their medical art instructor, content experts, and

additional resource people. Medical and neuroanatomical critiques are

provided online and offline by Ian Taylor M.D., Division of Anatomy, Department

of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, at U of T (Figure 7). Medical legal illustrators

in professional practice outside the local area also provide critiques

of student work in Knowledge Forum®. In 2001 and 2003, practitioners from

Sue Seif & Associates in Virginia critiqued students’ final visualizations

and provided online samples of their professional work. Students found

this experience very rewarding. Interestingly, the professionals did too

(Figure8).

The notion of what constitutes an authoritative reference or resource is redefined in an Internet connected world. It is easy to go beyond textbooks and static information, although the information may be equally of dubious quality. However, the Internet allows instant access to a myriad of information resources. Knowledge Forum® takes this one step further. Knowledge Forum® enables integration and communication with live resources. It enables feedback from busy local and distant professional experts. The knowledge building concept of promoting knowledge advancement between professional and student communities was evident in the course offered in 2003. Student innovation and professional expertise was distributed within and between these communities. Sue Seif indicated that the professional illustrators enjoyed the process and learned a lot. Successful engagement of students and practicing professionals in this learning environment raises new questions and opportunities for future curriculum development. Can professionals and students mutually benefit from working with ideas and collaborative problem solving in a shared conceptual space? Is it possible to develop a program that is offered concurrently for continuing professional development and masters level academic credit?

Embedded Transformative Assessment and Knowledge Building Discourse

According to Scardamalia and Bereiter (2002), knowledge building discourse

“results in more than sharing of knowledge; the knowledge itself

is refined and transformed through the discursive practices of the community.”

Ideas and visual artifacts are continually improved in the knowledge building

process. Continuous, anytime, anywhere constructive feedback is embedded

in the process. Collaborative feedback helps to transform ideas and becomes

evident in the artwork. Knowledge Forum® analytic toolkit (statistical

measures of collaborative knowledge building) is posted midway through

the course to provide concurrent feedback to students. The knowledge building

principle of “embedded and transformative assessment” characterizes

the learning process in this course. A culture of collaboration, openness

to feedback, and transformation of ideas generally characterizes BMC students.

Collaborative critiques, whether online or offline, involve an objective

stance toward self-assessment and reflection-in-action (Schon 1987). Students

work iteratively with ideas and visual artifacts. In 2003, students asked

to work iteratively with the course curriculum.

The Dynamic Knowledge Building Curriculum

The medical legal visualization class of 2003 asked for access to the 2002 Knowledge Forum® repository. The instructor’s first inclination was to deny access. The medical legal case was the same for both years. The process of visual problem solving was archived. The visual problems were solved. What would be gained by providing students with access to last year’s answers? We decided to treat this as a research question.

Current models of curriculum design advocate an iterative feedback loop, using students’ course evaluations to refine content, learning process, teaching methods, etc. This usually results in modest tweaking of the course curriculum. We call this the iterative curriculum. It is certainly better than the inert curriculum, which is not subjected to the feedback/iterative design loop.

The iterative curriculum usually spawns iterative ideas and incremental knowledge building advances (which on the whole are good). However, large mental leaps appropriate to education and work in the knowledge age need different supports — more like springboards for idea innovation. Rather than starting at the same point in each iteration, a knowledge-building curriculum should be a catalyst to idea innovation. Students should start to build on ideas at the cutting edge, where the work was last left off. The curriculum should be a dynamic springboard along a trajectory of knowledge creation. It should continually leverage ideas to support knowledge advancement. This is how researchers work. Students should become idea/knowledge researchers, not just idea/knowledge recipients. We posited that a dynamic curriculum could support knowledge advancement, continuous idea improvement, and innovation. The question of access to the 2002 Knowledge Forum® database provided an opportunity to test this hypothesis.

Collaborative Knowledge Building Innovation

BMC class of 2003 expressed the need to access to the 2002 database to build on previous ideas, to rise above what had been done before with the explicit goal of creating new ways of visually communicating complex medical information. The expressed goal is characteristic of knowledge builders, and is termed epistemic agency. It is the twelfth indicator of knowledge building (Scardamalia, 2002). The motivation to create new knowledge is clear.

Reference access to the Medical Legal Visualization 2002 Knowledge Forum® repository of ideas was provided to the class of 2003. Nine students participated in the medical legal visualization course. The course focused on visual problem solving and idea innovation. Two teams, with two and three students, were formed while four students worked individually. All students collaborated online and offline in ongoing critiques and in-class sessions. Individual and group processes, as well as evolution of ideas and artifacts were shared openly and visibly in Knowledge Forum® text and image note contributions.

Figure 9. MRI and illustrations can be merged and viewed through continuum

(© 2003 Doris Leung and Janice Wong)

Figure 9. MRI and illustrations can be merged and viewed through continuum

(© 2003 Doris Leung and Janice Wong)

Figure 10. Novel transition effects from patient photo to neuroanatomical injury

(© 2003 Danielle Bader, Julie Saunders, and Shelley Wall)

Figure 10. Novel transition effects from patient photo to neuroanatomical injury

(© 2003 Danielle Bader, Julie Saunders, and Shelley Wall)

Figure 11. 3D animation embedded in a Flash™ presentation showing normal anatomy

(© 2003 Jason Raine)

Figure 11. 3D animation embedded in a Flash™ presentation showing normal anatomy

(© 2003 Jason Raine)

Figure 12. 3D animation embedded in a Flash™ presentation showing normal clarifying patient specific injuries (© 2003 Jason Raine)

Figure 12. 3D animation embedded in a Flash™ presentation showing normal clarifying patient specific injuries (© 2003 Jason Raine)

No specific media requirements were stipulated, but all students chose to work digitally. Some began with hand renderings; others began with sketches in Adobe Illustrator™, Adobe Photoshop™, and schematics in Cinema 3D™. Final medical legal visualizations were realized as 2D illustrations, PowerPoint™ animations, and Flash™ presentations (one included embedded 3D animations). Patient MRIs were combined with medical illustrations, animations and text explanations. A novel slider to effect transitions from MRIs to illustrations was developed by a team of 2002 students in a Flash™ presentation. Animated transitions between primary evidence and visual representations were further enhanced in 2003 (Figure 9). One team used patient photography, in combination with illustrations in a Flash™ animation to produce the effect of visual transparency and simulated movement through anatomical layers (Figure 10). Another student created a 3D animation of the brain and embedded generic anatomical (Figure 11) and patient specific sequences (Figure 12) in a fully interactive Flash™ presentation. These conceptual ideas were noted as novel and innovative by various lawyers and medical legal artists, including those at Seif and Associates. To our knowledge, medical legal Flash™ presentations have not been used in Canadian or American courtrooms.

This conceptual innovation extends and redefines the use of medical legal visual presentations in pre-trial meetings and in the courtroom. Traditionally, medical legal illustrations are static presentations; animations are usually presented linearly on videotape. A Flash™ format provides a fully interactive, non-linear presentation. The locus of control and focus of presentation resides with the lawyer. The lawyer can select segments to be viewed, reviewed, and revisited as needed during a pre-trial meeting or during courtroom testimony.

Evidence of collaboration was seen in all final visualizations and reflective notes. Iterative design critiques, new software tools, and the concept of building on ideas created a synergy of enhanced pedagogic interactions and outcomes, resulting in idea innovation. The dynamic curriculum inspired knowledge building and novel solutions.

Student Satisfaction

A student satisfaction survey was administered at the conclusion of the course. The response rate was 100%. A five point Likert scale was used (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Results were tabulated in Microsoft Excel™. All nine students agreed or strongly agreed that they preferred a combination of face-to-face and online critiques. All nine students agreed or strongly agreed that Knowledge Forum®:

- Enabled more egalitarian student participation;

- Provided an important archived record of written comments for review; and

- Provided a process record for development of medical visualizations.

- Enabled more varied specialist/instructor participation (e.g., experts-at-a-distance); and

- Enabled more in-depth and analytical student-to-student critique comments.

- Resulted in critique comments that were more reflective online than in face-to-face sessions.

Conclusion

The collaborative culture of knowledge building and cutting edge tools creates a synergy of enhanced pedagogic interactions and outcomes, resulting in innovations in ideas and in medical legal visualizations. Scardamalia (2002) indicates “This culture captures the natural human tendency to play creatively with ideas and expands it to the unnatural human capacity to exceed the boundaries of what is known and knowable — to exceed expectations rather than settle into routines.” Building on ideas at the edge of knowledge supports the challenge of innovation. Knowledge building theory and Knowledge Forum® technology, together, create opportunities for dynamic curriculum design and leveraging ideas for collaborative innovation in the field of biomedical communications.

References

Bereiter, C. 2002. Education and mind in the knowledge age. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bereiter, C. and Scardamalia, M. 1993. Surpassing ourselves: An inquiry into the nature and implications of expertise. Chicago and La Salle, IL: Open Court.

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. in press. Learning to work creatively with knowledge. In Unraveling basic components and dimensions of powerful learning environments, eds. E. De Corte, L. Verschaffel, N. Entwistle, and J. van Merriënboer, EARLI Advances in Learning and Instruction Series.

Bloom, Benjamin S., ed. 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I, cognitive domain. New York: Longmans, Green.

Dewey, John. 1938. Experience and education. New York: Collier Books.

Donovan, M. Suzanne, Bransford, John D., and Pellegrino, James W., eds. 1999. How people learn: Bridging research and practice. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Knowles, Malcolm. 1975. Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Adult Education.

Sackett, D. L., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg W., and Haynes, R. B. 1997. Evidence based medicine. London: Churchill-Livingstone, 1997.

Scardamalia, M. 2002. Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of knowledge. In B. Smith. ed. Liberal education in a knowledge society, 67-98. Chicago: Open Court.

Scardamalia, M., and Bereiter, C. 2002. Knowledge building. In Encyclopedia of education, second edition. New York: Macmillan Reference, USA.

Schon, Donald A. 1987. Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Tiberius, Richard G. 1990. Small group teaching: A trouble-shooting guide. Toronto: OISE Press.

Whiteside, Alfed N. 1929. The aims of education and other essays. New York: The Free Press.

Acknowledgements

The Medical Legal Visualization Class of 2003, Danielle Bader, Marlene Herbst-Loth, Doris Leung, Camilla Matuk, Jason Raine, Julie Saunders, Gloria Situ, Shelley Wall and Janice Wong, is congratulated for the exceptional contributions to this course and to the field of practice.

The Medical Legal Visualization Classes of 2002, Sonya Amin, Marisa Bonofiglio, Teresa McLaren, Jason Sharpe, Mary Sims, Ken Vanderstoep, Yifeng Xuan, Cynthia Yoon, is gratefully acknowledged for the outstanding contributions to this course and for generating many of the foundational ideas.

Sue Seif & Associates are gratefully acknowledged for their valued feedback to the Medical Legal Visualization Classes of 2001 and 2003, and for their contributions to this research study.

Leila Lax (B.A., B.Sc.AAM, M.Ed.)

Leila Lax (l.lax at utoronto.ca) is an Assistant Professor in the Division

of Biomedical Communications. She is a research scientist with the Institute

for Knowledge Innovation and Technology and a member of the Wilson Centre

for Research in Education. She has received two teaching awards and one

innovation award for her integration of knowledge building/Knowledge Forum®

in her Medical Legal Visualization course. Leila has a B.A. in English

and Fine Arts, a B.Sc.AAM in Art as Applied to Medicine, a M.Ed. in Higher

Education (with a concentration in Health Professional Education and a

minor in Computer Applications). She is currently pursuing a doctoral

degree focusing on interprofessional knowledge building. Leila’s

research interest is the design, development and evaluation of Internet-based

collaborative learning environments for health professional education.

Ian Taylor (M.B., Ch.B, M.D.)

Dr. Taylor received his degrees from the University of Manchester. He is Director of the FitzGerald Academy, the Course Director of Structure and Function in first year Medicine and has been very involved in curriculum development and implementation in the pre-clinical years. Dr. Taylor teaches all subjects of the discipline to a variety of classes ranging from first year Physical and Health Education, to residents in Orthopaedic Surgery. His research interests are experimental Embryology and Teratology, particularly the normal and abnormal development of the heart and face.

Linda Wilson-Pauwels (AOCA, B.Sc.AAM, M.Ed., Ed.D.)

Linda Wilson-Pauwels is Chair of the Division of Biomedical Communications

(BMC), Department of Surgery and Director of the Master of Science in

Biomedical Communications (M.Sc.BMC) program. She is a visual communicator

with advanced degrees in higher education. She is a tenured, full Professor

in BMC with cross-appointments in the Centre for Research in Education

and Sheridan College’s School of Animation, Arts & Design. Wilson-Pauwels

is co-author of Cranial Nerves and Autonomic Nerves both published by

B.C. Decker Inc.

Marlene Scardamalia (Ph.D)

Marlene Scardamalia is a tenured Professor at the Centre for Applied Cognitive Science, Dept. of Curriculum, Teaching & Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, at the University of Toronto. She holds the Presidents Chair in Education and Knowledge Technologies and is the Director of the Institute for Knowledge Innovation and Technology at OISE/UT. Marlene Scardamalia has numerous publications and is acknowledged, along with Carl Bereiter, for the development of Knowledge Building theory and Knowledge Forum® technology. She guides a large international network of researchers and is the recipient of many educational research grants.